The Mojito

1 teaspoonful of sugar

Juice of one lime

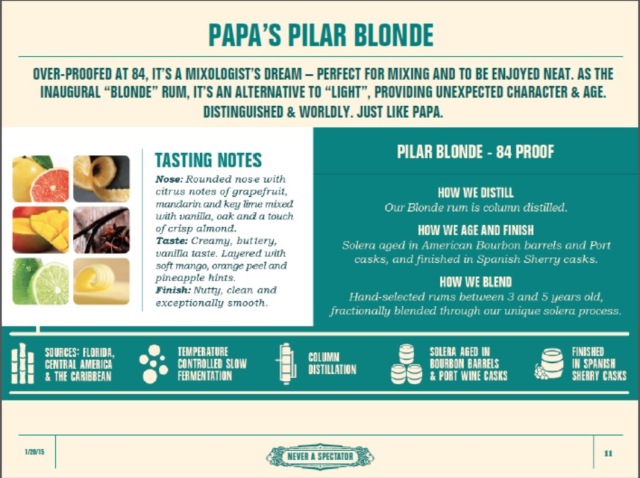

1.5 oz Papa’s Pilar Blonde Rum

1-2 oz sparkling water

4-5 mint leaves

Shake all ingredients (except for seltzer) well with ice, strain into an ice-filled Collins glass, then pour 2 oz. seltzer water into shaker to rinse ice (and chill seltzer), then strain into glass. Stir, garnish with a mint sprig and lime shell, and serve.

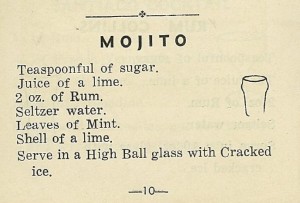

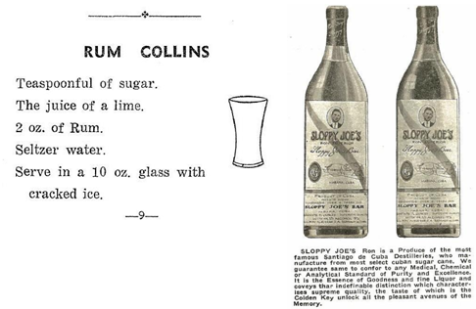

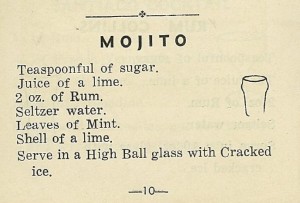

Recipe adapted from Sloppy Joe’s Cocktails Manual 1939. Note, I make mine a little differently, I shake rather than muddle the mint. Why? Who wants great globs of mint clogging up your straw? Further, my method of rinsing the ice with seltzer not only chills the seltzer but also releases flavor clinging to the ice remaining in the shaker.

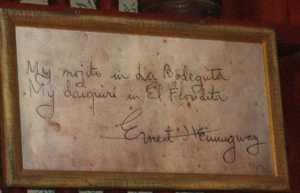

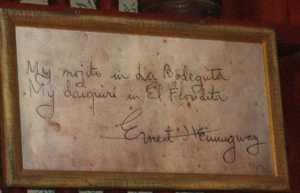

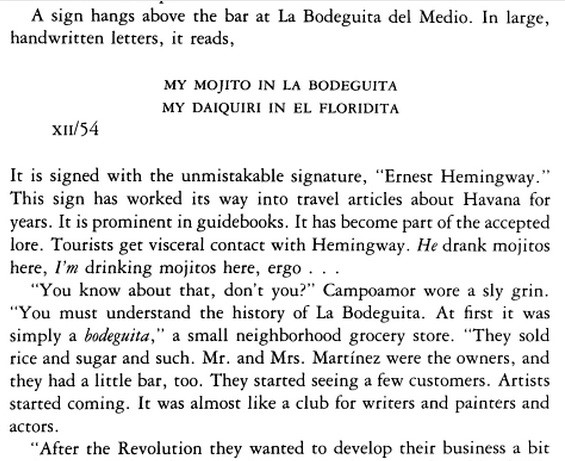

The birth of a myth, the allegedly “signed by Hemingway” sign hanging on the wall at Havana’s La Bodeguita del Medio, and the daily hordes of tourists who want to drink their authentic Hemingway Mojito since, after all, it was his favorite drink! Not.

As they say, you can’t prove a negative; how can you possibly prove that something didn’t happen? You might ask, what on earth does this have to do with Hemingway? Well, it concerns the mojito, and all the claims you’ll see about it being Hemingway’s favorite drink. Although I can’t prove it, I simply don’t believe that Hemingway was much of a mojito drinker, notwithstanding numerous claims to the contrary. But I can’t prove it.

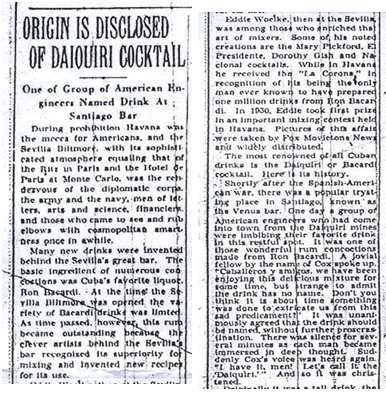

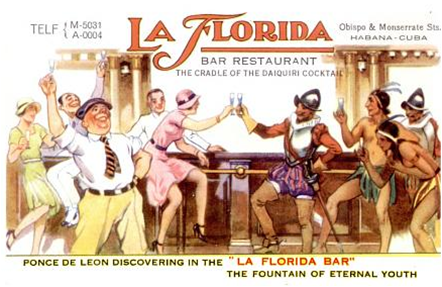

Numerous claims? Well, there’s a little joint in Havana called La Bodeguita del Medio. On the wall behind the bar is a framed piece of butcher paper, allegedly written by Hemingway. It reads, “My Mojito in La Bodeguita My Daiquiri in El Floridita.” That simple little inscription has not only launched a thousand claims that “Hemingway’s favorite drink was the Mojito,” but it’s also made La Bodeguita quite a lot of money from visiting tourists, as have many other watering holes in Havana, or Key West, or Miami…. If I had a dollar for every book or Web site that claimed the Mojito to be his favorite drink, or the drink “most associated with” him, well… For example, the bar menu for the chain restaurant Cheeseburger in Paradise says that the Mojito “was a favorite drink of author Ernest Hemingway who made the bar La Bodeguita famous for them after writing about the mojitos he drank there.” Oh? He wrote about them? What, in a novel? Short story? Esquire article? Oh, butcher paper, really? If you repeat a lie often enough it becomes the truth. Kind of like that story about all those bloody six-toed cats in Key West being descendants of a cat given to Hemingway by a sea captain. He didn’t have cats in Key West, he had them in Cuba. But this is about Hemingway’s drinks, not his cats.

Lining up the Mojitos for a new batch of suckers, … er, patrons who wish to experience a true Hemingway-channeling moment. Sorry (not sorry).

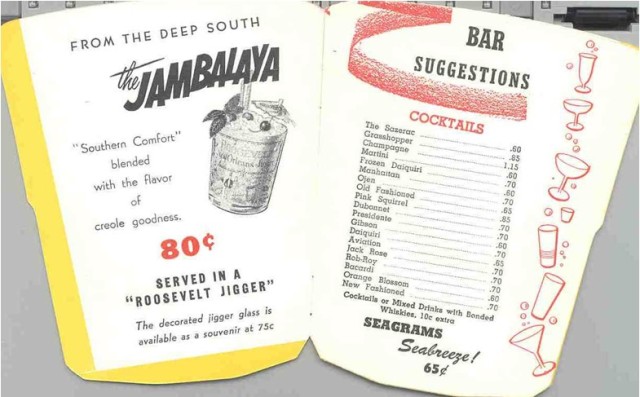

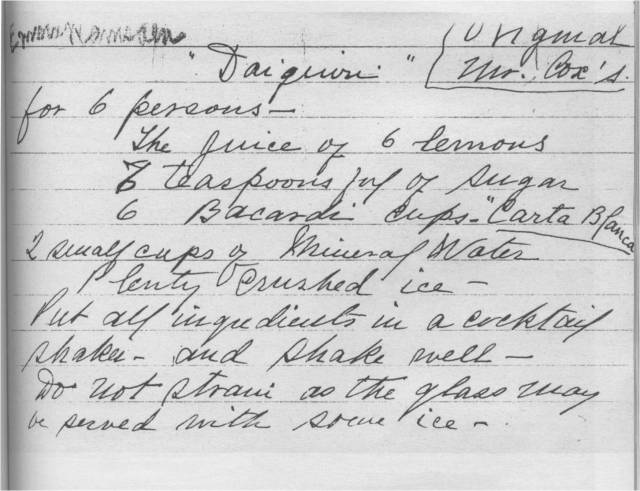

Mojito recipe from 1939 Sloppy Joe’s (Havana) cocktail guide, from collection of the author

Why so skeptical in the first place? As noted in every other chapter in this book, I can either place the particular drink into Hemingway’s hands, from biographies, memoirs or letters, or into his character’s hands, from his prose. Heck, if Hemingway wasn’t so fond of writing about what he drank, well, I wouldn’t have written this book, now would I? If he drank it, he generally wrote about it, somewhere. Not so with the Mojito. In fact, I’ve not yet encountered a single reference to either the drink, or the Bodeguita, in all of my research, which spans about 20 years. Let me qualify that; I did find one. Indeed, jai alai player Jose Andres Garate, a close friend during the ‘40s and ‘50s, said that he “drank with Papa at the Floridita many times and ate oysters with him at Ambos Mundos Hotel.” When asked about the Mojito story, he replied, “I’ve never heard of La Bodequita (sic) del Medio.”[i]

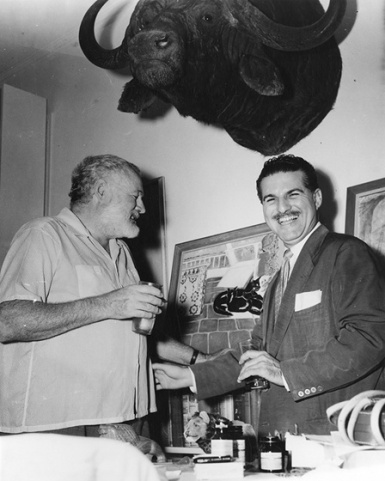

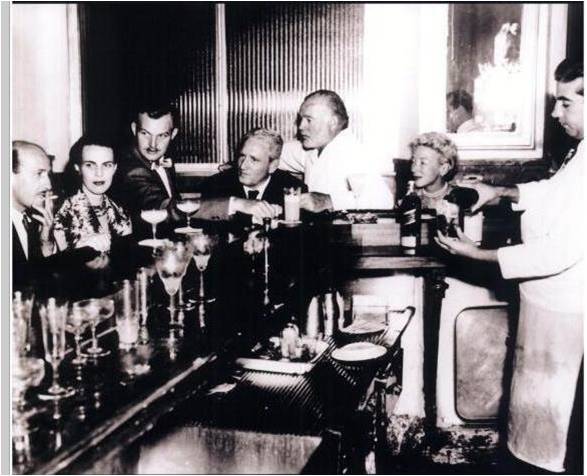

Further, there are countless photos of Hemingway at other Havana watering holes, such as the Floridita, Sloppy Joe’s, the Club Puerto Antonio, and at other places worldwide, like Harry’s Bar and the Stork Club. Any photos of Hem in the Bodeguita? Ixnay.

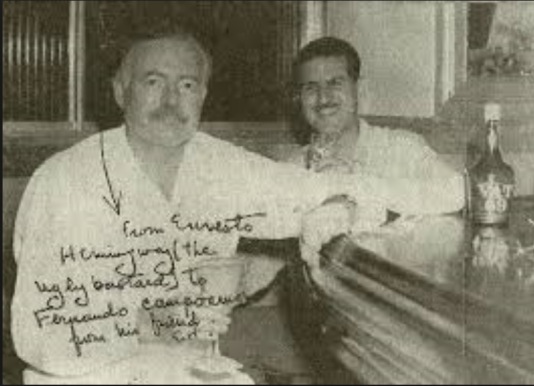

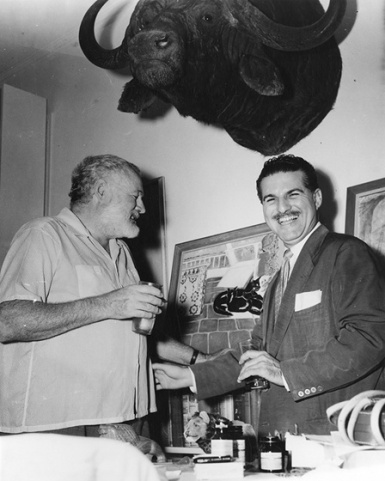

But the most damning evidence against the whole “Hemingway loved the Mojito and he drank them at La Bodeguita” story comes from the man who concocted the whole myth! Indeed, several books have asserted that the whole thing was a publicity stunt, cleverly concocted by Cuban journalist Fernando Campoamor, along with the bar’s owner. According to Campoamor, they hired a calligrapher to forge Hemingway’s handwriting, and “(t)he little joke grew into a big lie.”[ii] And a great many pesos, it seems. The galling thing is that Hemingway and Campoamor were friends. The plot was hatched in the years following Hemingway’s death; Papa won’t mind, he’d see the humor and value in it, I can hear Campoamor rationalizing.

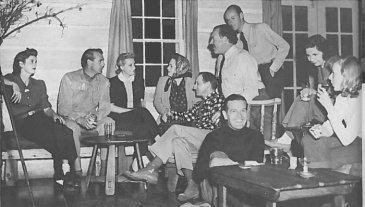

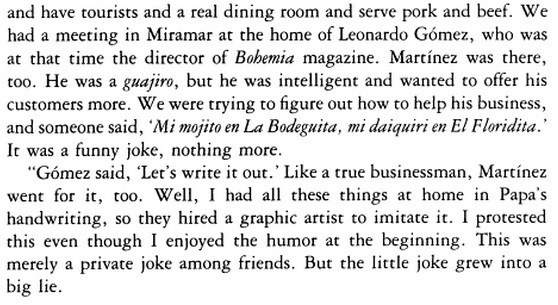

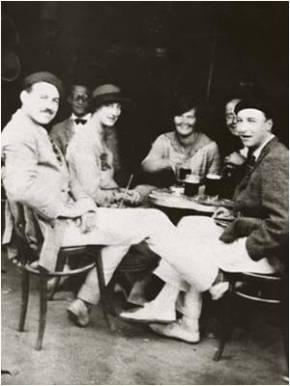

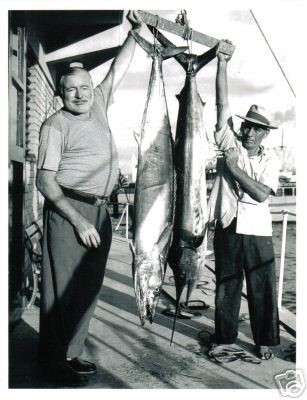

Hemingway and Campoamor saring a laugh, and a drink (though I don’t see any mint, do you?)

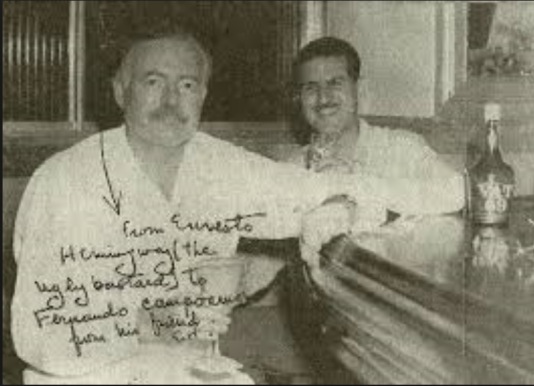

Hemingway and Campoamor at the Floridita (that’s definitely a Daiquiri Papa is holding, not sure what the bottle of Scotch is doing there). “From Ernesto Hemingway (the ugly bastard)” he signs it.

What follows is an excerpt from Tom Miller’s excellent book, Trading With the Enemy.

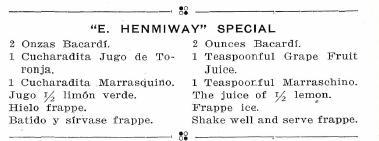

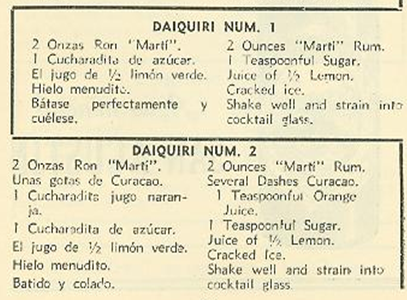

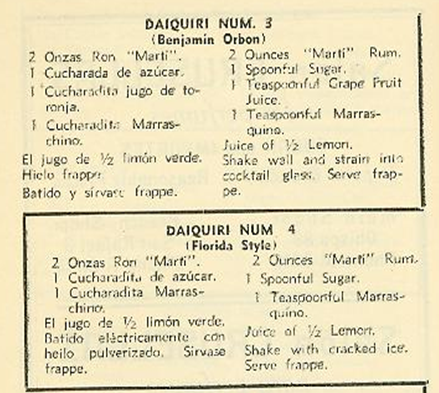

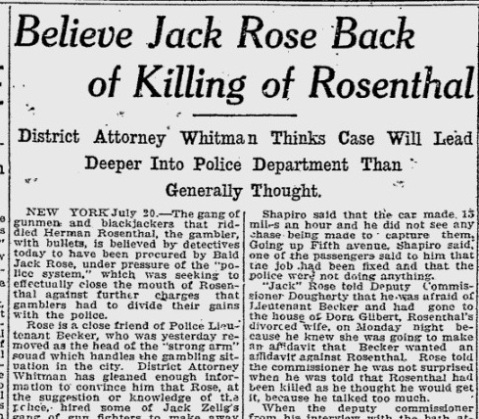

As for the drink itself, well, Hemingway simply didn’t like sweet drinks, and the Mojito (which usually packs an ounce or so of simple syrup) is a sweet drink. In his later years, with concerns about diabetes and sugar intake, he typically avoided such drinks. As he noted in Islands in the Stream, he loved to drink “these double frozens without sugar. If you drank that many with sugar in it would make you sick.” In fact, when you look at the other drinks Hemingway wrote about, you just don’t see too many sweet drinks. The Jack Rose does come to mind, but that was from 1926’s The Sun Also Rises, written long before the 27 year old writer was worried about sugar. By the mid- 30s, however, we’re seeing his penchant for sugar-free drinks, such as his E. Henmiway Special (a Daiquiri with maraschino liqueur in place of the sugar), the Death in the Gulf Stream (Holland gin, lime and bitters. “No sugar. No fancying.”), and the Irish Whiskey Sour. He once complained to his friend A.E. Hotchner that one of the reasons he didn’t like dining at other people’s homes was that he couldn’t trust the food and drink. On one occasion, they served sweet champagne, which he had to drink to be polite, but it took a week to get it out of his system.[i]

I’m not alone in my skepticism. The late Hemingway scholar Matthew J. Bruccoli observed, “I do not have any evidence that Hemingway ever drank that particular cocktail,” though “it is a safe generalization that Hemingway tried every cocktail ever mixed.”[ii] In The Hemingway Cookbook, Craig Boreth names a subchapter “The Myth of the Mojito.” Further, I’ve asked noted Hemingway historian Brewster Chamberlin for his views on the actual signed inscription. He’s the Archivist for the Key West Art and Historical Society (the island’s main museum), and has developed an extensive chronology of Hemingway’s life. Brewster began by noting that he’s spent countless hours poring over the log books of Joe Russell’s boat Anita and Hemingway’s Pilar, most of which is written by Hemingway, and he’s gained quite a level of familiarity with Papa’s handwriting. Said Brewster: “I have carefully examined the handwritten note attributed to Hemingway and I am convinced that he did not in fact write it. The handwriting is not his.”[iii]

Forgery? Publicity stunt? Who knows? Who cares? I’d just like to see the whole “Hemingway’s favorite drink” rubbish put to rest or, at least, the favorite part. Mind you, I have nothing against the Mojito, it’s a perfectly lovely drink, when made correctly, with fresh lime juice, not lemon-lime soda, and with just a trace of mint, not muddled clumps like Sargasso seaweed. I make them for my wife now and then with mint from our herb garden. I just don’t think they were among Hemingway’s favorite drinks, so I therefore offer it to you, dear reader, with a rather strong caveat.

Not only that, here’s a very similar drink I’ll offer to you that I do know that Hemingway enjoyed, I give you the Gregorio’s Rx:

Gregorio’s Rx

1 oz honey syrup (1:1 mix of honey and water)

1 oz fresh lemon juice

4 mint leaves

1 oz Papa’s Pilar Blonde Rum

2 oz sparkling water

Add all ingredients except for the sparkling water to a shaker with ice. Shake very well for 15 seconds. Strain into a glass with fresh ice. Add sparkling water to shaker, swirl it around, then strain it into the glass. Stir once or twice, garnish with mint sprig.

This is a drink concocted by Gregorio Fuentes, a longtime crewmember on Hemingway’s fishing boat Pilar. He was more than just a first mate, cook and bartender; after all, in his will, Hemingway left his beloved boat to Fuentes. When it became obvious that its maintenance was too much for a humble fisherman to handle, Fuentes donated the boat to the Cuban government. Not missing a chance to gain some good PR, and of course because it was the right thing to do, Fidel Castro gave Fuentes a new fishing boat. Fuentes was born in the Canary Islands, of Spanish extraction, and lived to be 104 years old. Many believe that Fuentes is one of two or three Cuban fisherman who formed a composite for the character of Santiago in The Old Man and the Sea, another being Carlos Guitierrez.

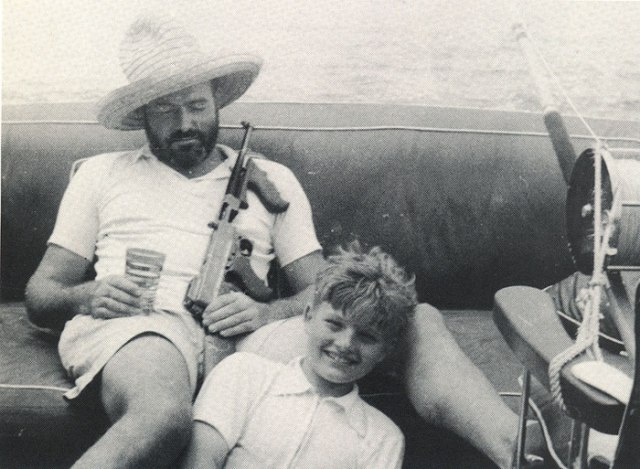

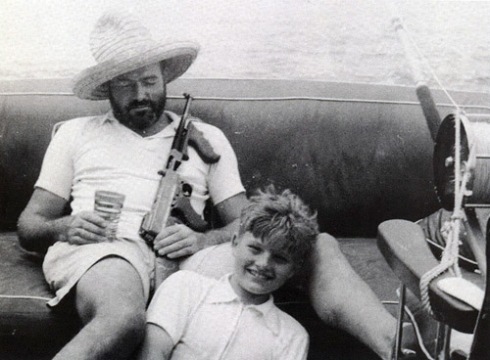

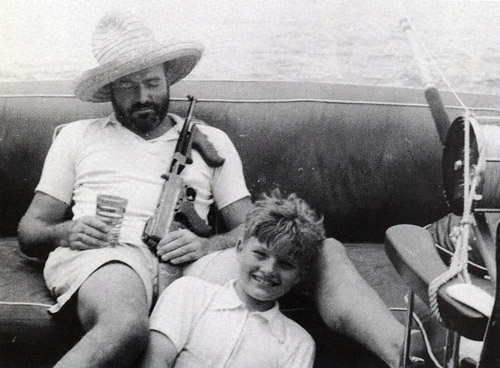

Hemingway and Gregorio Fuentes

While at sea, “Hemingway gave full command of the bar to ‘Gregorine,’ as he called Gregorio. As they sailed past the Morro of Havana, Hemingway would invariably say: ‘Captain Gregorine, please take charge of the Ethyline Department.’ Gregorio had his rules in this area, claiming “that a drink should be held in the hand no longer than half an hour. Once the sun makes it lukewarm, it should be discarded.”[iv]

“It was a pleasure to work for Papa. I was the skipper and I also cooked and served the drinks….I enjoyed being with him, and he was a real friend.” Gregorio Fuentes

As for this drink, it seems that “Gregorio had his own special prescription, which he considered very effective to prevent or cure a cold: ‘Take a clean glass and put two tablespoons of honey in it, add the juice of two lemons, a mint leaf, two ice cubes and rum to taste. Nothing like it,’ he says.”[v]

I know what you’re thinking, Gregorio’s drink sounds an awful lot like the Mojito, doesn’t it? Indeed, it has honey in place of the sugar. It’s not clear if “lemons” actually means lemons, or limon verde, i.e., lime, as has happened before where things get lost in translation (see the Daiquiri). It’s a very nice drink either way. Cheers!

SIDEBAR: Hemingway and Prohibition

According to Gregorio Fuentes , not only did Hemingway partake of bootleg booze during Prohibition, and not only did he consort with rumrunners like Josie Russell, Hemingway himself was a bootlegger! More on this in a moment, but first a word about The Noble Experiment.

Prohibition went into effect in 1920, and extended nearly to the end of 1933. Perhaps a statement on America’s overall ambivalence toward the Volstead Act, it didn’t seem to have too great an effect on Hemingway. It seems a bit ironic that it began the year he turned 21. At 19 he was serving in the ambulance corps in World War I Italy, getting a taste for a variety of potent potables. Back in the States, though he temporarily lived in a largely dry household, he didn’t seem too concerned about the coming crackdown. In a letter to his Red Cross friend Jim Gamble, he notes that America “isn’t such a bad place now with the exception of the coming aridity.”[vi] According to biographer Carlos Baker, “[h]e gaily predicted that Chicago would never go dry,”[vii] and laid in a good supply in his Oak Park bedroom. “On the left is a well-filled bookcase containing Strega, Cinzano Vermouth, kümmel, and martell cognac,” he bragged to Gamble. “All these were gotten after an exhaustive search of Chicago’s resources.”[viii]

During the course of Prohibition, Hemingway either lived in a place that didn’t have it (Paris), or didn’t particularly recognize it (Key West). In Paris, unlike many other American expatriates, he wasn’t necessarily there for the booze or the cafés; he went there to further his writing career (though it no doubt improved its “livability” in his eyes). And Key West was nearly as free and easy as the Left Bank, this according to a 1940 newspaper account:

“Key west has never felt the restraint of prohibition or gambling laws. It has more saloons and jooks than you can shake a well-rounded stick at, and most of them advertise a ‘club in rear’ where crap games, chuck-a-luck, and slot machines are open to all comers.”[ix]

By 1928, Hemingway had moved to what was at the time the southernmost town in the U.S., a burg well described by his friend John Dos Passos:

“There were a couple of drowsy hotels where passengers on their way to Cuba or the Caribbean occasionally stopped over. Palms and pepper trees. The shady streets of unpainted frame houses had a faintly New England look. Automobiles were rare because there was no highway to the mainland, only the causeway that carried the single-track railroad. The Navy Yard was closed down. The custodian used to let us go swimming off the stone steps in the deep azure water of the inner basin. You had to watch for barracuda. Otherwise it was delicious. There was really abundant fishing on the reefs and in the Gulf Stream. A couple of Spaniards ran good little restaurants well furnished with Rioja wine. Nobody seemed ever to have heard of Prohibition or game laws. The place suited Ernest to a T.”

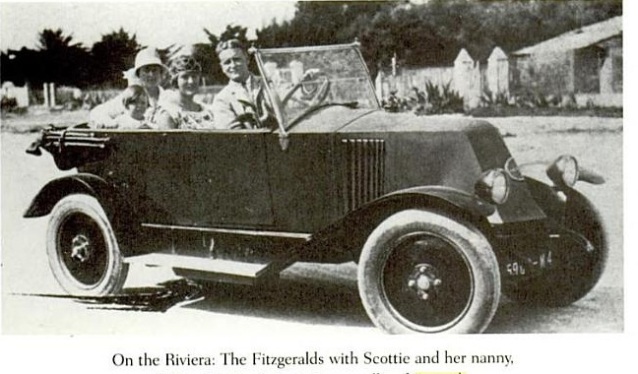

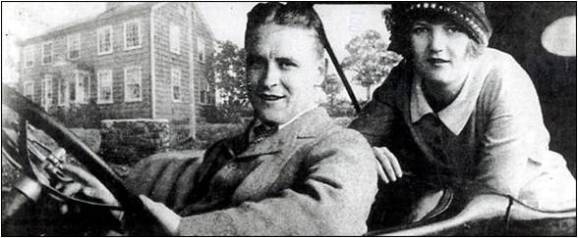

Hemingway and Dos Passos, the good life in Key West

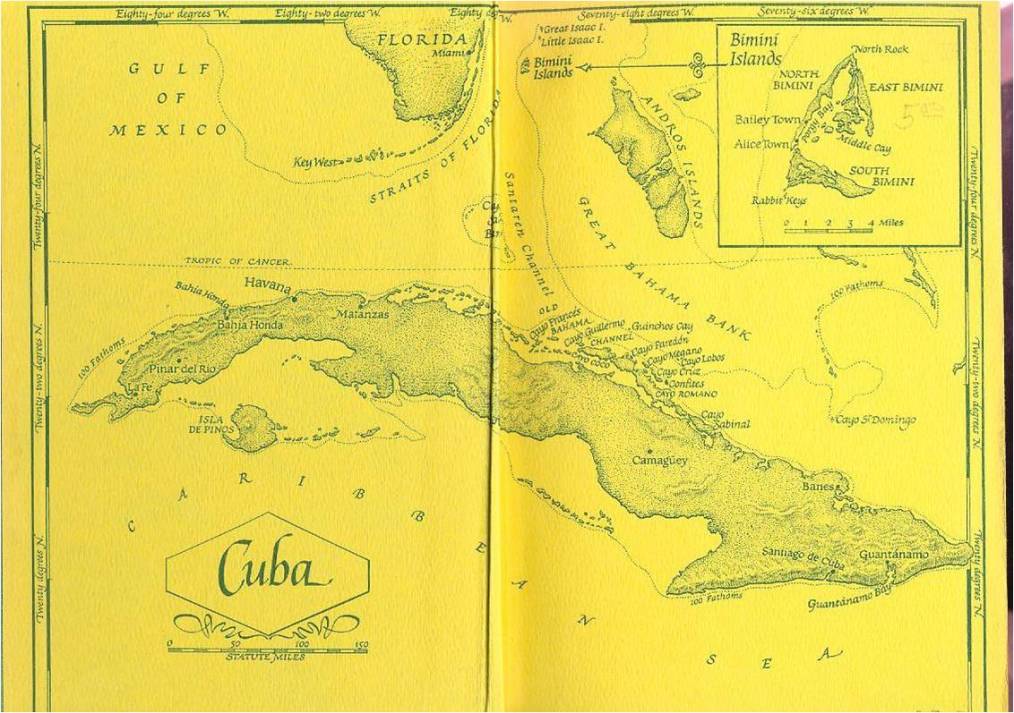

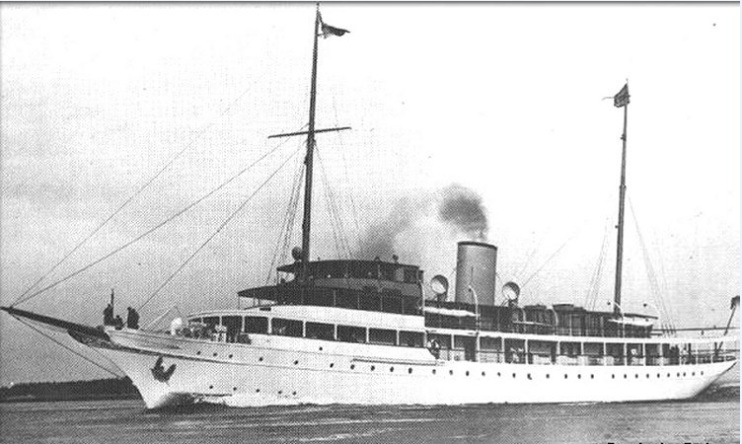

There was more there to drink than Rioja. Hemingway soon befriended Joseph “Sloppy Joe” Russell, and availed himself of “Josie Grunts’” services. It’s said that they met when Hemingway was able to purchase bottles of bootleg Scotch from him. According to some sources, Russell made more than 150 rum-running trips from Cuba to the Keys in his boat Anita which, until he bought Pilar, also served as Hemingway’s primary fishing boat. Russell explained his tactics:

“We loaded our whisky right in the Havana harbor and cleared our cargo in the legal way,” Joe said. “The American consul would tip off the officers and they’d be waiting for us on the other side. But we’d stick around Havana for a week and they’d get tired of waiting for us. Then we’d go across. Well, the consul finally got wise to what we were doing and got a rule passed ordering us to leave the harbor within 24 hours after clearing. After that we just didn’t bother about clearing. We loaded our liquor 12 miles below Havana and came across when we pleased.”[x]

Hemingway described his friend Josie’s exploits, this from a letter to his cousin Bud White, January 29, 1931:

“There is a bootlegger here with damned good fishing boat – 34 foot – Redwing motor – cabin cruiser type – that we can live aboard in Havana harbor. He knows Cuban coast and has made many trips – can make Havana from here in 10 hours in her or a little less – he will look after all formalities – we can fish tarpon in Havana harbor and drink there – go down coast to little fishing village and fish giant marlin from there – he says we can bring a load & as much liquor as we want back and we can dump it along in outer keys and then go out later and bring it back – you can take all you want 2-3 suitcases back with you on train with no trouble – they have no search nor bother.”,

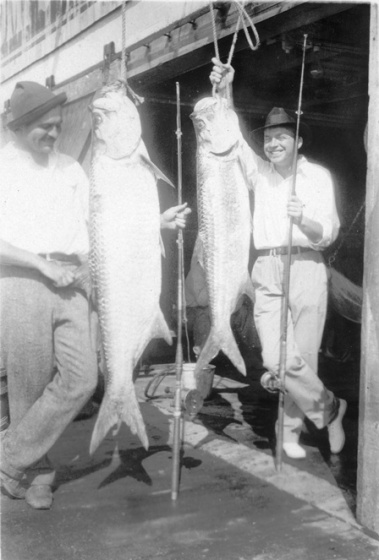

Hemingway (striped shirt) after a successful day at sea on Anita, with its owner Joe “Josie Grunts” Russell, owner of Sloppy Joe’s.

And according to Gregorio Fuentes, Hemingway himself tried his hand at rum-running:

“During Prohibition, Hemingway went to see [Joe] Russell and told him: ‘I’m broke, lend me your boat.’ Russell and Hemingway made a deal, and the writer went to Havana and managed to get around 600 or 700 cases of cognac from Recalt’s, 24 bottles to the case. The cognac cost them 40 cents a bottle, and sold in the United States at $3.50 each. … Hemingway smuggled the ‘goods’ from Playa de Jaimanitas. He and Russell agreed on the day and place to meet in jurisdictional waters. They had a prearranged system of signals, using red, white, and blue lights. According to Fuentes, that was how Hemingway made enough money to go to Europe and Africa.” [xi]

I believe the story, but am a little dubious of the “around 600 or 700 cases of cognac” claim, simply because I can’t see the 38-foot Pilar holding that much while crossing the Gulf Stream and making the arduous 10 hour, 90 mile voyage from Havana to Key West. I don’t doubt Fuentes’ veracity, either; as a wise man once said, it’s not a lie, if you believe it. He may have gotten that number from Hemingway, who liked to, shall we say, embellish. It is a good story, though.

[i] David Nuffer, The Best Friend I Ever Had (self published, 1988), at p 100.

[ii] Tom Miller, Cuba: True Stories (San Francisco, Travelers’ Tales, Inc., 2004), 146; Alfredo Jose Estrada, Havana: Autobiography of a City (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008), 87. Tom Miller, Trading With the Enemy: A Yankee Travels Through Castro’s Cuba (New York: Basic Books, 2008), 168.

[i] A.E. Hotchner, The Good Life According to Hemingway (New York, HarperCollins Publishers, 1008), 101

[ii] As quoted by Eric Felten, A Cuban Summer Cooler,Wall Street Journal, August 4, 2007

[iii] Brewster Chamberlin, Author of “A Chronology of the Life and Times of Ernest Hemingway” (forthcoming), Paris Now and Then (2004), The Time in Tavel (2010) and other books.

[iv] Norberto Fuentes, Hemingway in Cuba (New Jersey: Lyle Stuart, Inc., 1984), 101-102

[v] Norberto Fuentes, Hemingway in Cuba (New Jersey: Lyle Stuart, Inc., 1984), 101-102

[vi] Along With Youth (), 116

[vii] Carlos Baker, Ernest Hemingway, A Life Story (), 61

[viii] Along With Youth, 117

[ix] From Aug 6, 1940 St Petersburg FL Independent

[x] From Aug 6, 1940 St Petersburg FL Independent

[xi] Toni D. Knott, One Man Alone – Hemingway and To Have and Have Not (Lanham, MD: University Press of America, Inc., 1999), 73-74